In this reflective essay, Valencia Abbott, the North Carolina and National History Teacher of the Year for 2025, explores how place-based, inquiry-driven history instruction empowers students to see themselves as historians. Centered on local civil rights history, her work demonstrates how community-rooted learning builds critical thinking, empathy and civic readiness.

Abbott has over two decades of experience in education and currently serves as the social studies department chair and a civics teacher at Rockingham Early College High School (Rockingham County Schools). She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science, a master’s degree in liberal studies, and a post-baccalaureate certificate in African American studies from UNC Greensboro, along with add-on licensure in academically/intellectually gifted education from Duke University.

In addition to her most recent titles, her dedication has earned her numerous accolades, including the 2024 Civil Rights/Civil Liberties Excellence in Teaching Award and the 2024-2025 RECHS Teacher of the Year honor. She is also a 2024 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Teacher Fellow and serves on multiple advisory boards, underscoring her commitment to education and civil rights.

Few decisions are more intimidating than choosing to become a public school teacher at 40. When firmly devoted to seeing it through, the process of gaining teacher certification was no joke. Since I had enough undergraduate credits, I was told I should be certified in English and social studies, but I graciously turned them down. To this day, I still don’t know the proper use of a semicolon, and I also adore reading so much that I didn’t want it to become jaded for me. But with social studies and history, it is a passion; it is an integral part of not only my personal education journey but also my teaching history. As with history, the more you know, the more there is to know.

I was born and raised in Rockingham County, North Carolina. Like many rural communities, our history often existed in fragments. Stories were passed down at kitchen tables, church homecoming services and funerals. These stories hinted at something deeper. Elders knew more than what appeared in textbooks. I sensed early on that what we were taught about the past rarely explained why things looked the way they did around us. History, for me, became a way to ask better questions.

With over 20 years of teaching in the bag, the last 13 at Rockingham Early College High School, I have come to understand that teaching history is less about delivering content and more about creating space for inquiry, for truth-telling, and for connecting the local to the national. I understood that if history was going to matter to my students, it had to start close to home. It had to be stories of self, so they could understand their place in the world.

While I am deeply honored to be awarded the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History’s North Carolina History Teacher of the Year and then the National History Teacher of the Year (NHTOY), it was a validation of the work that I am already doing. Even if the outcome of the award had been different, it would not have changed my trajectory in the classroom, in history, with the students or in the community. We, as social studies teachers, have to get out of the mindset that history is just taught in the four rooms of our classroom.

The United States Supreme Court case Griggs v. Duke Power Company (1971) established the legal doctrine of “disparate impact.” This fundamentally reshaped civil rights law. Yet locally, it was almost invisible. Before 2018, most people in Rockingham County did not know that one of the most significant employment discrimination cases in U.S. history originated here. By making local history visible, two historical markers have been installed. My students were actively involved at every step of the process. One student told me she would never have asked her grandmother about segregated schooling if not for this project. Another uncovered a photograph of a plaintiff whose story had been nearly lost to time. A trio of students expanded this work into a National History Day documentary. And for the first time in my school district’s history, students advanced not only to the state competition but also qualified for the national contest. Together, we learned that history is not fixed. It is constructed, contested and deeply human. We also learned that rural communities are not footnotes to the national story.

This work reflects what is possible when history instruction centers on local context, primary sources and student voice. They are often the engine of change. Since 2012, I have served on the Program Committee of the Museum and Archives of Rockingham County (MARC). This work has further reinforced for me the importance of carrying history beyond the classroom threshold and into the community.

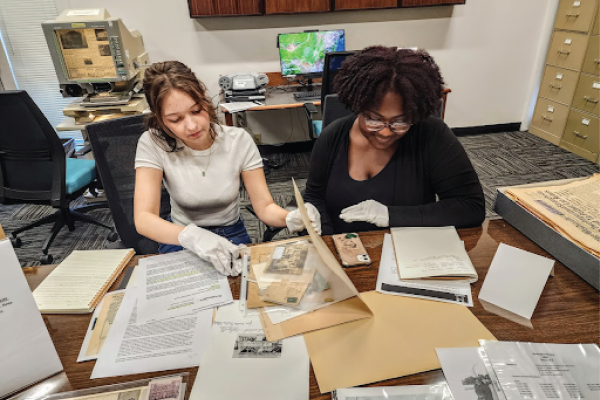

My NHTOY application highlighted my participation in the National Council for History Education’s Rural Experience in America initiative. This project was funded by the Library of Congress. I had the opportunity to build a long-term, inquiry-based project that placed students at the center of historical discovery. Over three years, we examined rural education during Jim Crow, the lives of Black World War II veterans who were plaintiffs in the Griggs case and the role of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in shaping national civil rights strategy. What made this work transformative was not just the subject matter, but the method. Students conducted oral histories. They handled archival materials that had not been viewed for decades. They wrestled with primary sources that lacked neat explanations.

We live in a moment where information is abundant. Yet understanding is fragile. Students are surrounded by narratives, some credible, some distorted, many designed to provoke rather than inform. In this context, history is not about nostalgia or celebration. It is about critical thinking. Teaching students how to analyze sources, evaluate claims and understand context equips them with tools that extend far beyond the classroom. History teaches discernment.

History also teaches empathy. When students examined Black veterans who fought for democracy abroad and returned to segregation, or saw how educational barriers shaped employment, they saw how lives are shaped by systems. That awareness matters. It pushes students to ask not just what happened, but who benefited, who was excluded and why patterns persist.

Finally, history gives students a sense of agency. When young people discover that ordinary individuals from their own county played a role in shaping national law, it reframes what is possible. They learn that change does not only come from famous names or distant places. It can come from communities like theirs. It comes through persistence, organization and belief in justice.

Teaching history today is not easy work. It requires navigating complexity, discomfort and competing narratives. But it is necessary work. History helps students understand who they are, where they come from and what responsibilities they carry forward. It reminds us that democracy is not inherited automatically. It is built, challenged and sustained by informed citizens.

For me, teaching history has always been an act of coming home: to place, to people and to purpose. The past is not behind us. It is with us, shaping every choice we make. My task and my privilege are to help students see that clearly. I trust them with the truth.